if you ask most fishers around the Chesapeake Bay about cownose rays, they’ll typically respond with some version about how much they don’t like the rays, and how frequently they catch them while fishing for other species (this is called “bycatch”). All of these unwanted captures over the years have only furthered a negative reputation about cownose rays, a member of the eagle ray family whose numbers began to increase dramatically along the East Coast in the late 1900s. In 2007, a research paper was published that stated the rays had begun to increase in abundance because there were fewer large sharks around to control them – and furthermore, it implicated cownose rays in the decline of commercial shellfish throughout the Mid-Atlantic. Quickly, the cownose rays became villains, and the hunt was on. “Save the Bay, Eat a Ray” became the slogan for a regional push to eradicate cownose rays, including bowfishing tournaments. The problem is, while it’s not clear why the rays have increased so much, they just simply don’t eat very many of the shellfish that are commercially valuable. Despite this, the hunt was on.

By 2016, other scientists had begun to question the 2007 story entirely. In addition to noting that cownose rays don’t eat many of the commercially important shellfish, they also questioned whether the increase in cownose rays could have been caused by a loss of large coastal sharks as the 2007 paper had claimed. They based this on a different set of shark population surveys, but also largely on the fact that coastal sharks don’t eat cownose rays frequently. However, it’s important to realize that predators affect their prey in more ways than just eating them – the mere presence of a predator can affect where a potential prey animal goes, what it eats, how it behaves, and ultimately, its overall health and fitness. So while large coastal sharks may not have been directly eating a lot of cownose rays in the past, it could be that when more sharks were present, the resulting stress on cownose rays may have limited their reproductive potential and/or influenced their movement patterns away from coastal estuaries like the Chesapeake Bay.

With this is mind, we are taking another look at the trophic cascade proposed in 2007, using 15+ years of additional data and integrating stress physiology to try to understand what led to the regional increase in cownose rays. For the first time, we will complete a cownose ray stock assessment to understand just how many there are in the population. And in the field, we are collecting blood samples from wild-caught cownose rays, trying to determine whether cownose rays experience chronic stress in the presence of predators like sharks. We will repeat this work at the cownose ray overwintering grounds in Florida, where local shark populations are more abundant than in the Chesapeake, to compare the stress response across a gradient of risk. Although the fishing pressure on cownose rays has decreased, and many bowhunting tournaments have since been banned, there is still an unregulated fishery for cownose rays, and it’s important to get this information to managers sooner rather than later.

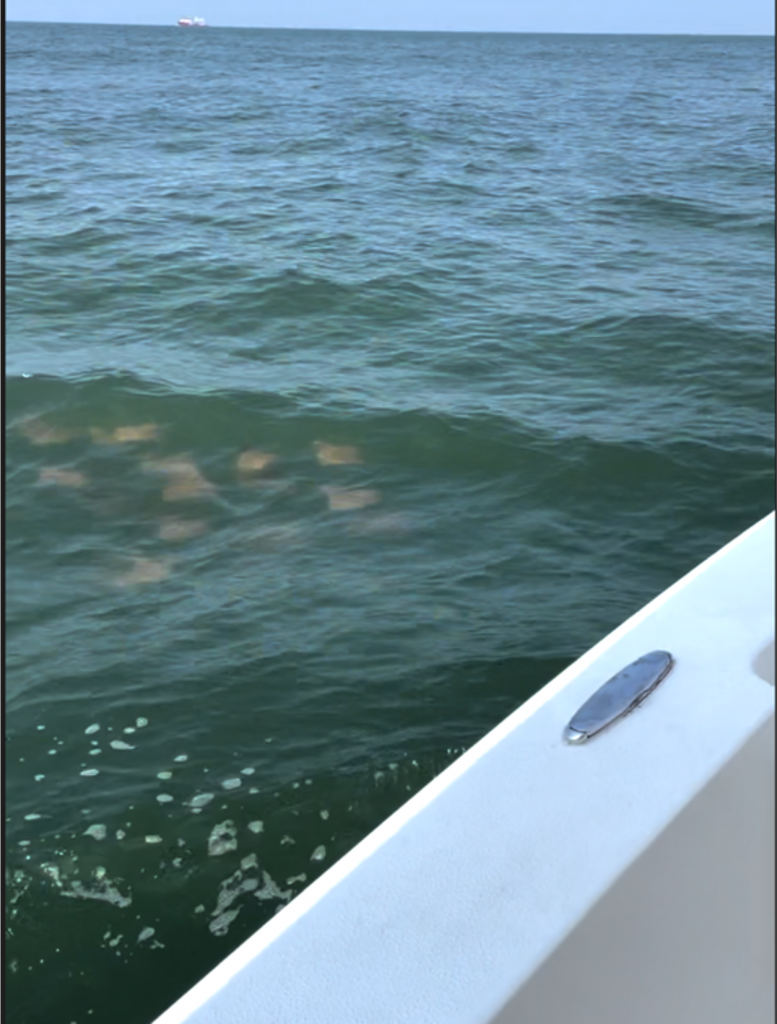

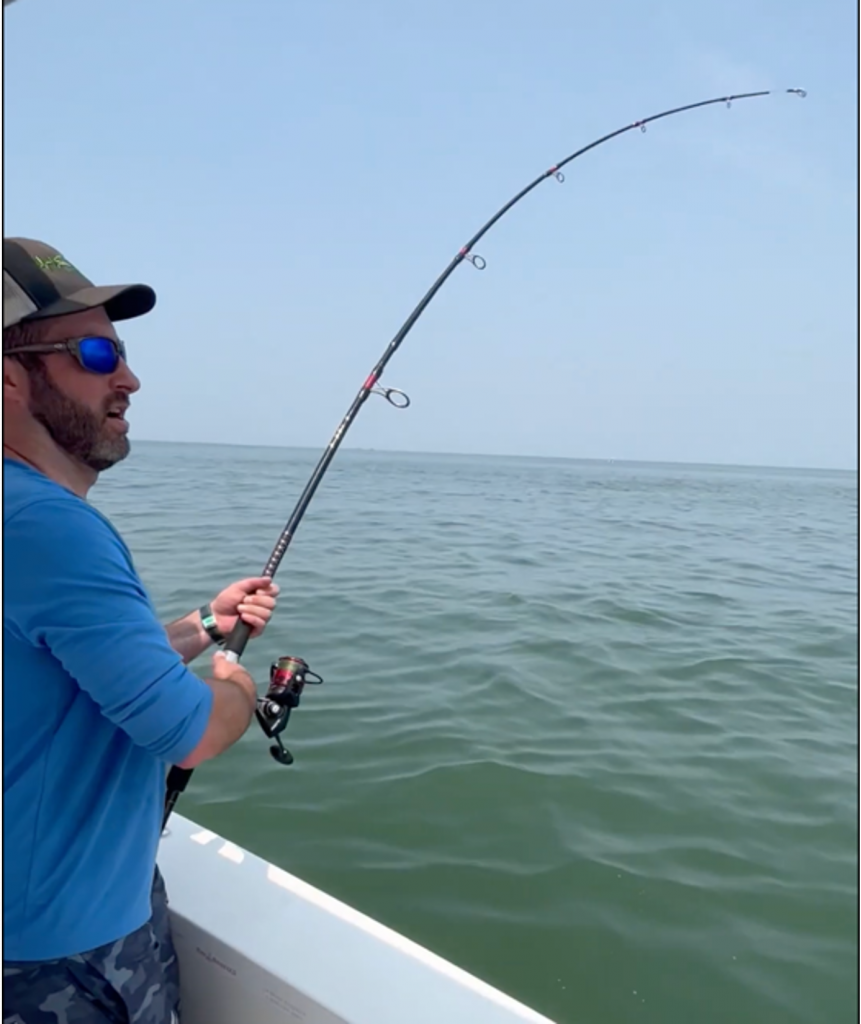

Catching cownose rays is no easy feat! Although many fishers complain of accidental captures, so far, it has been challenging to capture rays when on the lookout directly for them. The rays are highly mobile, so it can be difficult to find a fishing approach that works. We’ve employed a combination of cut bait and lures, and on our third day on the water, we finally landed one! We saw a large school in front of the boat and casted lures to the front – as I pulled my lure through the school, the rod suddenly bent over as the ray took the lure and instantly ran off 100 yards of fishing line before I could slow it down. A few minutes later, we used a net to secure the 90-cm wide ray and bring it into the boat for processing. Both of us were stunned at how big and heavy the ray was, but we quickly got to work. Unfortunately, we were unable to collect a blood sample from this specimen, as the vasculature was difficult to find and the seas were rough, making everything more difficult. We did collect a fin clip which can be used for genetic and stable isotope analysis to learn more about this annual visitor to Chesapeake Bay.

While on the water, we also used the time to conduct a range of other studies to detect cownose rays and otherwise. We deployed baited remote underwater video (BRUV) stations to collect underwater footage of cownose rays and collected and filtered ambient seawater for environmental DNA (eDNA), which is free-floating DNA that can be collected and sequenced to assess the potential presence of different species. We also used a drone to search for schools of rays as well as to collect imagery in support of an anti-poaching autonomous drone we are developing. Overall, a very exciting couple days of the water around Virginia Beach and Hampton!